Consider these possible connections between Mary, the Patron Saint of the cathedral, and the labyrinth at Notre Dame de Chartres.

View the slides from a presentation on The Chartres Cathedral, Mary, and the labyrinth.

Mary as Birth-giver and Mother

In some discussion about the labyrinth, Mary is equated with Ariadne of the original myth. Mary, as the mother of the Church, is understood to hold the thread that keeps Christians from losing their way. Gilles Frésson links the ancient red cross on the vault high above the entrance to the labyrinth with the piece of metal (which he believes is present to recall Ariadne’s thread) underneath it on the cathedral floor. See Frésson, Gilles. Mars-Avril 1990. “A propos du labyrinthe.” Notre Dame de Chartres: 16-18.

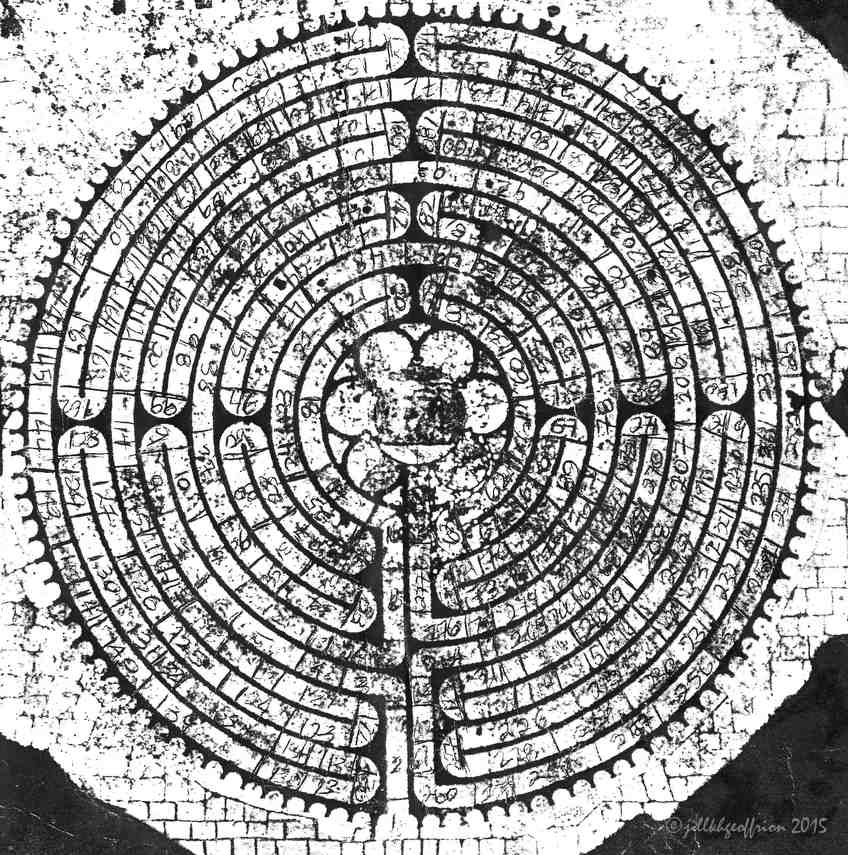

Some see a correspondence in the number of stones of the labyrinth to the days of human gestation. In Chartres, this could be a subtle echo reminding pilgrims of Mary’s pregnancy with Jesus. See Roger Joly. (1999). Une Nouvelle Lecture pour Le Labyrinth de la Cathédrale de Chartres. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie d’Eure et Loir, 63, 202-231. Page 220 is of particular interest.

In talking with both catholic and Protestant pilgrims, I have heard several mention experiencing the labyrinth as, “Mary’s breast” (le sein de Marie), a place of maternal comfort and reassurance.

The six-petalled rose

In medieval times the rose symbolized the Virgin Mary.

“…the meaning of the petals relates…to Mary, to whom the cathedral is dedicated. One of the most elementary geometrical designs is one circle surrounded by six others, all exactly the same size, all just touching each other… Seven, then, is the relevant number with regards to petal design, even though we see only see six petals. Seven, it seems, is the only number in the first ten numbers (1-10) that neither generates nor is generated by another number via multiplication. …it neither begets nor is begotten. For that reason, it has been know since ancient times as “the virgin.” Seven is the number of virginity. Chartres Cathedral is dedicated to the Virgin Mary because of the great hope that she could act as intercessor and help one attain Paradise. The center of the labyrinth represents Heaven, the goal of our earthly journey. The chance of arriving there is enhanced by Mary’s help and her status. It makes sense that the geometry of the petals, therefore, is based on the number of the Virgin.” Robert Ferre. Constructing the Chartres Labyrinth. An Instruction Manual. St. Louis, MO: One Way Press. (2001) 21.

The Stained Glass Windows of Chartres, Mary, and the Labyrinth

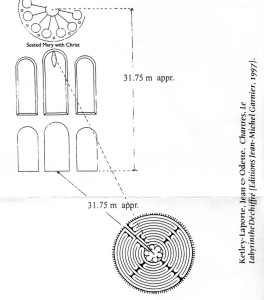

Images of Mary in the stained glass that surrounds the labyrinth relate to it in meaningful ways. For instance, John and Odette Kelley-Laporte in Le Labyrinthe Déchiffré describe a relationship between the light entering the cathedral through the western central lancet window on the feast days of Mary (the Dormition on August 13, 1194, or the Assumption on August 15th of that year) during the construction the church that determined the placement of the labyrinth and thus the geometry of the entire cathedral. See pages 63-65.

“Le 22 août (qui correspond au 15 août, jour de l’Assomption, du calendrier julien utilisé au Moyen Age), un rayon de soleil relie la Vierge de la verrière occidentale au centre du labyrinthe. Or la verrière fut placée quarante ans avant le labyrinthe actuel. On notera aussi que la hauteur du centre de la rose est sensiblement égale à la distance qui sépare le labyrinthe du massif occidental. La rose, elle, fut mise en place vingt ans après le labyrinthe.” Page 64.

While walking the labyrinth, many images of Mary are visible including:

To the east of the labyrinth:

The apsidal image of Mary as a throne for Jesus who is sitting on her lap blessing on the top of the East-central window (above the choir).

The Annunciation of Jesus’ birth to Mary in the East-central window (above the choir).

The Visitation of Mary and her cousin Elizabeth in the East-central window (above the choir).

To the west of the labyrinth:

Mary in the Tree of Jesse (Ancestors of Jesus). Twelfth-century window (1140-1150) on the north side of the west wall.

The Annunciation in The Life of Christ Window. Twelfth-century window (1145-1155), the central window on the west wall.

The Visitation of Mary and Elizabeth in the Life of Christ Window.

The Nativity: Mary, Jesus, and Joseph in the Life of Christ Window.

The Kings Visit Jesus and Mary in the life of Christ Window.

The Flight Into Egypt: Mary, Jesus, and Joseph in the Life of Christ Window

The Return from Egypt: The Holy Family in the Life of Christ Window

Jesus blessing while sitting on Mary’s Lap in the Life of Christ Window

Mary standing below the cross of Jesus in the Passion and Resurrection Window (1145-1155), on the south side of the west wall.

Mary holding Jesus’ hands as his body is taken off the cross in the Passion and Resurrection Window.

Mary watching the anointing and entombment of Jesus in the Passion and Resurrection Window.

To the south of the labyrinth:

Nursing Mary and Jesus in a clerestory window (1205-1215) above the labyrinth.

Mary holding Jesus, a sculpture on the fifteenth-century organ above the south nave.

The symbolic “shirt of Mary” on the Bishop’s pulpit (south side of the nave) above the labyrinth.

The flight from Israel to Egypt in the St. John window in the south aisle.

Mary’s death as witnessed by the mourning disciples. The death and glorification of Mary window (1205-1215) in the south aisle.

Mary’s soul being received by Jesus. The death and glorification of Mary window.

Mary’s casket being carried by the disciples to its resting place. The death and glorification of Mary window.

The entombment of Mary’s body by the disciples. The death and glorification of Mary window.

The assumption of Mary into Heaven. The death and glorification of Mary Window.

South rose: Mary with 7 gifts of the Spirit

South rose: Mary, seated with Jesus

Symbolic representation of Mary’s veil on the wooden pulpit to the south of the labyrinth

In the aisles on the side of the nave:

Southside: Flight to Egypt bottom of St. John window

Southside: Death and Assumption of Mary Window (Various scenes)

Southside: Coronation of Mary (Vendome Chapel)

Southside: Miracles of Mary window (Various scenes)

Northside window nearest the crossing: Redemption Window: Mary during Jesus’ crucifixion

The stations of the cross that are placed in the north and south aisles

Pheobe Griswold spoke of her experience of Mary while walking the labyrinth. “I turned toward the high altar. There in a window above the altar was Mary and her story, the annunciation, and visitation… Mary gazed out, straight down the nave to her son at the end of the Church. Like a giant tie-rod that holds a structure together, Mary’s gift to us became vividly apparent to me. I saw what Henry Adams meant when he wrote, “It is about Mother and Son.” Reflection: The Labyrinth of Chartres. Anglican Theological Review (Winter 2001).

Gematria and Mary

While I am not familiar with the practice of Gematria, I pass on these thoughts from John James, the Australian Architect who has studied the cathedral extensively. See James, John. 1982. The Master Masons of Chartres. NY: West Grinstead Publishing and 1977. “The Mystery of the Great Labyrinth: Chartres Cathedral.” Studies in Comparative Religion 11:92-115.

As the labyrinth has four quarters, each quarter plus one spells MARIA EST ASSUMPTA. This is from the ancient way divines would combine the meanings of words with the letters through a process called Gematria. In this modality each letter is given a number, starting with ‘A’ as 1, and using the 22 letters of the Roman alphabet. Adding or subtracting one from a phrase in Gematria is acceptable, as it represents unity, and therefore the godhead itself.

The entry being to the left of centre there are 55 cogs on one side and 57 on the other. These two numbers spell ECCLESIA and DOMINE, while the whole including the two halves which add one cog spell both CHRISTUS and MARIA MATER DEI.

The tracks and the number 35. The labyrinth has 31 curved tracks and 4 straight ones, 35 altogether. This spells BVM, which is short for Beata Virgo Maria, to whom the cathedral is consecrated.

There are 28 half-round changes of direction and six quarter changes, 34 in total. This is the number of ANNA the mother of Mary, while both 6 and 28 are the first two Perfect Numbers. Together they add up to 34 which is one off BVM, and one off MV, or Maria Virgo. Half of 34 is seventeen which is the letter R standing for the Resurrection. 37 times 3 is 111, which we met earlier. Twice 35 is 70, which spells JESUS, Thrice is 105, which is TRINITAS, and four times is 140, or CHRISTOS EST.

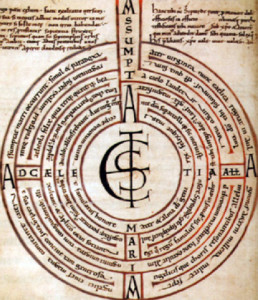

For further study: The eleventh-century manuscript in the Cambridge University Library, Kk 3.21. (See Kern, 141, figure A.)

This labyrinth features a 6-circuit Chartres-type pattern, with a joyous poem winding through the paths, announcing Mary’s assumption into Heaven. The words “Assumpta Est Maria” (“Mary is assumed”) travel down the vertical axis of the equilateral cross, with “Est” (“is/ exist”) in the center; “Ad Caeletia Atta” (“To the Heavenly Father”) traverses the horizontal axis. The poem, part exaltation and part entreaty for favorable intervention gives a completely new perspective on the labyrinth and its relationship to Christian spirituality. This is the first known connection of the labyrinth to Marian worship; despite the occasional presence of Ariadne, the figures associated with most other contemporary labyrinths – Theseus, the Minotaur, Daedalus, and Minos – were male. This manuscript also provides a definitive link between the concept of the labyrinth and heaven; the poem describes “the hall of the sevenfold heaven” (Kern 141), and the accompanying text claims that “wisdom has structured this city, which a sevenfold circle surrounds, and one and the same exit and entrance opens it with open approaches and closing, closes it again” (Kern 141). The connections between the labyrinth, Mary, and the heavenly city become even more pronounced as one delves into the symbology of the church labyrinths of the later Middle Ages. Kristin Doll, Hic Habitat Minotaurus: Transformation of the Labyrinth from Pagan Myth to Medieval Manuscripts, Page 12. Unpublished Paper.

Translation of the Poem from Kern, 141: Mary is assumed into heaven, Alleluia. The virgin mother now reigns in the court of heaven, surrounded by a thousand soldiers of the eternal army. The angel citizens, with the accompaniment of a great throng, meet the mother after the assumption and at the same time they exalt the marvelous offspring above the race of David, with dwellers in heave and angelic choirs re-echoing alleluia for their fellow-citizen, so noble is she…

Bibliography:

Doll, Kristin. (2003). Domus Deadeli: Elements of Sacred Symbolism in the Labyrinth of Chartres. Unpublished paper. Includes an in-depth discussion of Mary, the labyrinth, and the heavenly city.

Doll, Kristin. (2003). Hic Habitat Minotaurus: Transformation of the Labyrinth from Pagan Myth to Medieval Manuscripts. Undergraduate Paper for Literature and Religion (U of Minnesota, Prof. Stephen Daniel). Literature. University of Minnesota. Unpublished.

Dubosc, Georges. Première parution dans le Journal de Rouen du 5 avril 1920 sous le titre : Le football de Pâques dans les églises du Moyen-Age. Texte établi sur l’exemplaire de la médiathèque (Bm Lx : norm 1496) de Par-ci, par-là : études d’histoire et de moeurs normandes, 3ème série, publié à Rouen chez Defontaine en 1923.

Ferré, Robert. (2001). Constructing the Chartres Labyrinth. An Instruction Manual. St. Louis, MO: One Way Press.

Frésson, Gilles. Mars-Avril 1990. “A propos du labyrinthe.” Notre Dame de Chartres:16-18.

Griswold, Pheobe W. (2001). Reflection: The Labyrinth of Chartres. Anglican Theological Review(Winter 2001).

Joly, Roger. (1999). Une Nouvelle Lecture pour Le Labyrinth de la Cathédrale de Chartres. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie d’Eure et Loir, 63, 202-231.

Kern, Hermann. (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Designs and Meanings over 5,000 Years. New York: Prestel.

Ketley-LaPorte, John & Odette. (1997). Chartres: Le Labyrinthe Déchiffré: Éditions Jean-Michel Garnier.